™

™TRADITIONAL MOUNTAINEERING

™

www.TraditionalMountaineering.org

™ and also

www.AlpineMountaineering.org

™

™

™

FREE BASIC TO ADVANCED

ALPINE MOUNTAIN CLIMBING INSTRUCTION™

Home

| Information

| Photos

| Calendar

| News

| Seminars

| Experiences

| Questions

| Updates

| Books

| Conditions

| Links

| Search

![]()

Leave no Trace with Restop bags

Lara Usinowicz sent me the following technical seminar notes:

Hello. My name is Lara Usinowicz. I am the Sales

and Marketing Manager for a company called Restop. We make a bag containment

system for human waste to comply with the outdoor ethics of Leave No Trace. I

would like to spend the next hour talking about the issues of human waste in the

wilderness and the solution that Restop provides.

There are two primary concerns with the disposal of human waste in the

backcountry: human health problems as a consequence of either direct contact or

contamination of drinking water, and aesthetic concerns of visitors who find

improperly disposed waste—what I like to call the “eeewww” factor. Nothing worse

than getting to your pristine camping site in the wilderness to find a pile from

the last visitor or “paper flowers”, a ridiculous euphemism for toilet paper

left behind. I think one of the problems with dealing with human waste is many

people’s discomfort with talking about shit. Maybe if we referred to human waste

as “shit” and toilet paper as “shit paper”, it would sound more vulgar and folks

would be more apt to think that it is disgusting to leave your pile of shit and

shit paper in the woods. As I like to say, “Get your shit together!”

In addition…the transmission of disease-causing pathogens (bacteria, viruses,

and protozoans) from human feces is a serious health concern. Over 100 bacteria,

protozoans and viruses are potentially present in human feces and capable of

causing illness. Common parasites include Giardia lambia, cryptosporidium parvum,

and entamoeba histolytica. Viral infections include hepatitis A, gastroenteritis

caused by rotavirus, Norwalk-like agents, and viruslike particles.

Giardia appears to be the most common animal parasite affecting humans in the

U.S. Giardiasis can be transmitted through fecal contamination of food and water

or through direct fecal-oral contact. Though waterborne transmission of Giardia

is believed to be the least common mode of transmission overall, it is the

primary concern of backcountry travelers because many Giardia infected areas

exist in the backcountry. Studies have found that in Colorado, 40-45% of beaver

were infected, 48% of muskrats and as many as 20% of cattle were shedding cysts.

Dogs may be important reservoirs for human Giardia—they can defecate in or near

water and roll in feces, thus helping spread cysts.

However, humans are considered the most important component in the epidemiology

of girardisis. One milligram of feces may contain 300 million cysts and

ingestion of even a few cysts may lead to infection.

The most common symptoms that one can expect when infected with Giardia are:

diarrhea (7-10 days), abdominal cramps, nausea and/or loss of appetite,

flatulence or bloating, and fatigue. If Giardia is not treated, it will often go

away on its own but it can become a chronic problem—sounds like fun, eh?

Other parasites such as cryptosporidium parvum and entamoeba histolytica have

similar epidemiologies and similar fun, enjoyable symptoms.

The National Park Service hosts almost 300 million visitors to the National

Parks per year (does that mean 600 million pounds of waste)? Human waste is

easily processed where there is power, water, and plumbing. However, the

2,000,000 annual backcountry campers are entering pristine wilderness

environments where building flush toilets is not always feasible or desirable.

The mission of the NPS is to preserve “unimpaired the natural and cultural

resources and values of the national park system for the enjoyment, education,

and inspiration of this and future generations.” Based on this mission, removing

waste and a “leave no trace” policy is essential to backcountry settings. Siting

and maintaining these “backcountry” wastewater disposal systems is complex,

expensive, and sometimes physically challenging. Typically the only alternative

is to create a collection site where the human waste must be physically removed

and transported by backpackers, horse, or helicopters during and after the end

of the season.

Human feces can pose a problem not just from a public health perspective, but

will also introduce unnatural nutrients into the environment if not

contained/removed. To monitor these activities and provide public health

consultative services the U.S. Public Health Service entered into a Memorandum

of Agreement in November of 1955 with the Department of Interior. This has

allowed the NPS to provide routing, monitoring and oversight of wastewater

collection and disposal within the National Parks.

The methods used by parks range from cat holes, pit privy, bag systems, or more

complex systems such as composting toilets, dehydration or evaporative toilets,

septic tanks, centralized collection sites (river trips), and treatment plants.

Parks have spent much money, time and effort installing and maintaining these

systems in order to prevent disease transmission and provide an unimpaired

natural and cultural resource.

The World Health Organization estimates that the average adult produces about

one liter—some 2 pounds worth—of excreta per day, half of that being solid

waste.

How many people are here? So, as a group, we are producing __ pounds of waste

per day. And how many students do you take on each outing? We may each take just

a small group but he produces two pounds and she produces two pounds and so on

and so on…

For the sake of discussion, consider that in 2005, Grand Canyon National Park

counted 238,381 backcountry overnight stays. If most of those visitors stayed in

the park for 24 hours, that means that 120 tons of human urine and feces was

bequeathed upon the Grand Canyon backcountry in 12 months.

In the month of January, in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, there have

been 3,220 overnight stays, 2,311 of those in the backcountry. They’ve only had

to deal with one ton of excreta but that is in just one month and, in the month

of January, not exactly high season.

During the 2004-2005 season, 4206 people went to Aconcagua National Park in

Argentina to climb this 20,886 foot peak. The trek to the summit takes between

10 days and two weeks. I do not have exact statistics on how many people

summitted the peak so let’s say half of those people, so about 2000 were on the

peak for 10 days. Two pounds per day, 2000 people—4,000 pounds a day for 10

days…that’s going to pile up!

In Zion National Park, day use in the slot canyons totaled 13,365 people,

overnight use totaled 1452 people—and 2005 was a low use year due to high water.

In 2004, there were 17,166 people for day use and 3065 overnight users. These

numbers do not include one of most of the non-technical climbs including day use

of the lower Narrows. So the total is actually higher.

The Arkansas River in Colorado is the most heavily rafted river in the world. In

2005, there were 271,180 commercial user days and 30, 127 private boaters. While

the figures are for the entire Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area, Browns

Canyon, which is the most environmentally sensitive, has the most use.

I could go on and on with statistics but I think you get the idea. As more and

more people head into the wilderness, human waste is a growing problem and we

need to take responsibility for ourselves in the great outdoors. Recreational

use of the backcountry areas in the U.S. has increases significantly and is

estimated at 2 million visitor days per year.

There are areas where you can bury your waste. The proper method is to dig a

cathole 6 to 8 inches deep at least 200 feet from water, camp, and trails. After

use, cover and disguise the cathole and pack out all toilet paper and hygiene

products.

While digging a cathole is a viable option, it is interesting to note a

wilderness impact study commissioned by the Sierra Club in the 1970s. The

nonprofit organization wanted to find out what impact its organized “Sierra Club

Outings” backcountry trips were having on California’s Sierra Nevada mountains.

A group of researchers observed (from afar) the defecation practices of the

Sierra Club Outings participants—most of whom were traveling in large groups and

using latrines to do their business. The group leader would usually determine

where the latrine was dug, and the big hole was then the receptacle for all of

the group’s waste for, in most cases, less that 24 hours.

The researchers made a note of all of these latrine sites scattered across the

Sierras, then they went back anywhere from one to three years later and

uncovered the latrines to see what had happened to the feces. The researchers

found that the waste, along with the many resident bacteria, was alive and well

and had decomposed very little, if at all.

Another study about a decade later in Montana’s Bridger Range unearthed the same

truths—except this time the focus was on catholes rather than latrines.

Researchers from Montana State University buried bacteria-rich deposits of human

waste in cat holes that varied in depth from 2 to 8 inches and were located in

six different types of Rocky Mountain soil environments and elevations. When the

samples were dug up 51 weeks later, after one winter had passed, all the feces

remained a virtual playground for various disease-causing bacteria (namely E.

coli and salmonella).

The report, entitled “Potential Health Hazards from Human Wastes in Wilderness”

said, “The idea that shallow burial renders feces harmless in a short time is

fallacious.” It continued, stating, “Site did not make the difference that we

expected. The results seemed to apply to all elevations and exposures on the

mountain. From our data, it is unrealistic to hope for a rapid die-off of

intestinal bacteria in cat holes. Pathogens might be transferred to later

campers in three ways: direct contact with the feces, by insect, or by water.”

Both studies pointed out, however, that putting waste in cat holes was

preferable to a latrine because the smaller the fecal deposit, the greater its

contact with surrounding soil organisms and air, which are central to the

decomposition process.

Of course, there are then many areas where burying your waste is NOT an option.

These include:

HEAVY USE AREAS: at trailheads and other areas where digging a cathole might

entail digging up someone else’s waste

IN DEEP RIVER GORGES: where it is impossible to travel the required 200 feet

away from the river

ALONG ANY WATERWAY WHERE THERE IS ONLY SANDY SOIL which doesn’t have the

nutrients to decompose waste

IN CANYONS AND HIGH DESERTS: where the soil is also without the microorganisms

necessary to biodegrade human waste

ABOVE THE TREELINE: in any mountaineering or climbing venue where the soil is

too rocky to dig the required 6-8 inches fro a proper cathole.

That being said, a cathole is an option in some areas, but is it the best

option? Can we teach our students and get them accustomed at a young age to the

idea of “packing it out”? If there is a user-friendly and pleasant means to deal

with carrying out your waste, why not do it? While I condone any method of

carrying out your waste, whether it is a plastic baggie, a PVC tube, or the

“blue bag” that is offered on several mountaineering venues, such as Rainer,

compliance is an important issue so the method should be as pleasant as

possible.

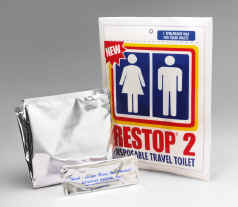

I’d like to introduce you to the Restop line of personal sanitation products…

Zion National Park hands out the Restop product with your backcountry permit.

They switched to another product, the Wagbag, due to its degradability but then

switched back to Restop because of problems with compliance. They were finding

that people were trying to “do the right thing” but, because of the odor issue,

were now leaving their bags of waste in the wilderness.

Mount Rainier provides a system known as “the blue bag.” It is basically a blue

plastic bag and the method is to defecate on the snow and then use the bag as a

mitt to pick up your waste. Then, you are to throw these bags into receptacles

on the mountain. This is a fine system but why should the National Park be

responsible for carrying out canisters of human waste. Why not empower the

individual to be responsible for him or herself and provide them with an

effective and inexpensive solution? In Grand Teton National Park, they used to

use the “blue bag” system. When the canisters were full, the Park Service would

helicopter them out. That came to a halt when one of the canisters was

accidentally dropped and the backcountry was littered with blue bags of human

waste. They now hand out the Restop product to visitors.

Western State College was involved with a cleanup expedition to Aconcagua last

January. Currently, the Park Service provides climbers with a cheap plastic bag

which has proven highly ineffective. The bags leak, stink and therefore, there

are issues with compliance—the bags of waste are often left behind. Who wants to

carry a smelly, leaking bag of shit in their backpack? This peak in Argentina

has become a virtual minefield of human waste and Restop provided the WSC

students with 250 Restop 2 bags to help educate climbers and guides. I am

currently working with the Park Service at Aconcagua to see if we can make the

Restop product part of the permit.

There are similar problems on other high peaks such as Mt. Everest and

Kilimanjaro as well as domestic areas like the 14ers (the peaks over 14,000

feet) in Colorado. In addition to high peaks, many rock climbing areas are

starting to put in requirements or suggestions to “pack it out.” There are often

facilities near sport climbing areas but “near” is still a quarter- or half-mile

away and “when nature calls”, often a half-mile walk is too far away. Restop

offers a great solution, “just in case”.

River runners (rafters, kayakers, and canoeists) have grown accustomed to the

idea of packing out their waste as it has been required for years. We need to

see a shift in consciousness in other outdoor communities before more of our

mountain, desert, and climbing areas turn into an “Aconca-ca”.

The Restop bags retail for $14.95 for a five-pack so they are an effective,

accessible means for everyone to take things into their own hands, so to speak.

We can each take responsibility for the wilderness or we can let it go to…well,

you get the idea.

Well, then, as environmental educators, I call on you to spread the word about

the effective and inexpensive means that Restop provides for you to “get your shit together”

Note: I met Lara at the American Alpine Club's Annual Meeting in Bend Oregon in 2007. She was talking to everyone about . . well you know. I think that Restop is a great product, technically better than the traditional blue bag. I have been trying to figure out how I could write this article for many weeks. I finally decided to print the entire technical story.

Lara pointed out that it was not necessary to have a companion hold the bag while you did your business. This had proved to be a difficult arrangement. It is now practical to poop on the paper provide and then bag the result, all while maintaining perfect privacy ;-)) It is best to carry the bagged poop safely on the outside of your pack, thereby proclaiming your Leave no Trace Ethics ;-)) --Webmeister Speik

American Mountain Guides Association writes the following:

When Nature Calls

As sponsors of Leave No Trace, The American Mountain Guides Association is

committed to minimizing impact on the backcountry when on their outings. As more

and more people head into the backcountry, the issue of human waste is a growing

problem and must be confronted.

The World Health Organization estimates that the average adult products about

one liter—some 2 pounds worth—of excreta per day, half of that being solid

waste.

For the sake of discussion, consider that in 2005, Grand Canyon National Park

had 238,381 backcountry overnight stays. If most of the visitors stayed in the

park for 24 hours, that means 120 tons of human urine and feces fell upon the

Grand Canyon backcountry in 12 months.

In the month of January, in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, there have

been 3,220 overnight stays, 2,311 of those in the backcountry. They’ve only had

to deal with one ton of excreta but that is in just one month and, in the month

of January, not exactly high season.

Then there is the case of Aconcagua, nicknamed “Acon ca-ca,” due to the

minefield of human feces upon the mountain. During the 2004-2005 season, 4206

people went to Aconcagua National Park in Argentina to climb this 20,886 foot

peak. The trek to the summit takes between 10 days and two weeks. If half of

those people summitted, that means about 2000 people were on the peak for 10

days. Two pounds per day, 2000 people at ten days each…that is going to pile up!

There are countless other areas that are being heavily impacted by human waste

and all of us have the responsibility to prevent another “Acon ca-ca.”

There are areas where you can bury your waste. The proper method is to dig a

cathole 6 to 8 inches deep at least 200 feet from water, camp and trails. After

use, cover and disguise the cathole and pack out all toilet paper and hygiene

products.

While digging a cathole is a viable option, it is interesting to note a

wilderness impact study commissioned by the Sierra Club in the 1970s. The

nonprofit organization wanted to find out what impact its organized “Sierra Club

Outings” backcountry trips were having on California’s Sierra Nevada outings.

A group of researchers observed the defecation methods of the Sierra Club

Outings participants—most of whom were traveling in large groups and using

latrines to do their business. The group leader would determine where the

latrine was dug, and this was then a receptacle for all of the group’s waste

for, in most cases, less that 24 hours.

The researchers made a note of all the latrine sites scattered across the

Sierras, then they went back anywhere from one to three years later and

uncovered the latrines to see what had happened to the feces. The researchers

found that the waste, along with the bacteria, was alive and well and had

decomposed very little, if at all.

Another study about a decade later in Montana’s Bridger Range discovered the

same truths—except this time the focus was on catholes rather than latrines.

Researchers from Montana State University buried bacteria-rich deposits of human

waste in catholes that varied in depth from 2 to 8 inches and were located in

six different types of Rocky Mountain soil environments and elevations. When the

samples were dug up a year later, after one winter had passed, all the feces

remained alive with various disease-causing bacteria (namely E. coli and

salmonella).

The report, entitled “Potential Health Hazards from Human Wastes in Wilderness”

said, “The idea that shallow burial renders feces harmless in a short time is

fallacious.” It continued, stating, “Site did not make the difference that we

expected. The results seemed to apply to all elevations and exposures on the

mountain. From our data, it is unrealistic to hope for a rapid die-off of

intestinal bacteria in catholes. Pathogens might be transferred to later campers

in three ways: direct contact with the feces, by insect, or by water.”

Both studies pointed out, however, that putting waste in catholes was preferable

to a latrine because the smaller the fecal deposit, the greater its contact with

surrounding soil, organisms, and air, which are central to the decomposition

process.

There are many areas where burying your waste is not an option. These include:

heavy use areas: at trailheads and other areas where digging a cathole might

entail digging up someone else’s waste; in deep river gorges: where it is

impossible to travel the required 200 feet away from the river, along any

waterway where there is only sandy soil which doesn’t have the nutrients to

decompose waste; in canyons and high deserts where the soil is also without the

microorganisms necessary to biodegrade human waste; above the treeline: in any

mountaineering or climbing venue where the soil is too rocky to dig the required

6-8 inches for a proper cathole.

While any method of carrying out your waste is better than the alternative,

whether it is a plastic baggie, a PVC tube, or the “blue bag” that is offered in

several mountaineering venues, such as Rainier, compliance is an important issue

so the method should be as pleasant as possible.

The Restop products offer a safe and sanitary means to deal with human waste in

the wilderness. The Restop 2 solid waste bag contains the odor as well as the

waste. Inside the bag is a powder, a polymer/enzyme blend, which biodegrades and

gels the waste, giving it EPA approval to be simply thrown away in the trash

after use. Restop provides the user with an inexpensive and effective means to

comply with the outdoor ethics of Leave No Trace.

The Restop bags retail for $14.95 for a five-pack so they are an effective,

accessible means for everyone to take things into their own hands. We can each

take responsibility for ourselves in the wilderness or we can let it go to shit…

The American Mountain Guides Association

American Alpine Club reports the following:

Waste Bag Programs Expanding

July 2007

The AAC's Restop human-waste bag dispenser at Lumpy Ridge,

Colorado. The AAC-built human-waste bag dispenser installed at the old Twin Owls

parking lot at Lumpy Ridge in Colorado is going through about 20 bags a week,

according to the National Park Service. Now, the NPS has approved a second

dispenser for Rocky Mountain National Park, to be installed at Chasm Lake, below

the Diamond on Longs Peak, in August. Greg Sievers, leader of the AAC’s Central

Rockies Section, commissioned the construction of two oak boxes for the bags,

and the section donated the first two cases of Restop 2 human-waste bags for the

pilot program. For more info, contact Greg Sievers.

The AAC is also working with Grand Teton National Park, hoping to provide

carry-it-out waste bags at the Grand Teton Climbers’ Ranch and the Lupine

Meadows trailhead, the primary access for the central Teton peaks. And this fall

discussions will be held with Yosemite National Park.

The AAC has been a leader in human waste-removal efforts for climbers since

2001, when the club provided seed funding for Denali’s Clean Mountain Cans

program. Climbers are now required to carry down their waste from Denali’s high

camp. The AAC also was a key backer of the Friends of Indian Creek’s

carry-it-out waste program.

http://www.americanalpineclub.org/pages/story/6/35

![]()

Read more . . .

Restop

Mountaineering Wag Bag solutions in 1985

TraditionalMountaineering in Central Oregon

Mountain Link's Robert Link throws a party in Bend Oregon

Dennis Hanson’s slide show of his trip to Cordillera Blanca in Peru

News Channel 21 interviews TraditionalMountaineering.org

Winter hiking in The Badlands WSA just east of Bend

Robert Speik interviewed for television program

Gearheads are prepared for every adventure

Mountaineering Blue Bag alternatives

Access Fund Sharp End Award goes to Robert Speik in 2000

Oregon State Parks thanks Robert Speik for his past service

Robert Speik instructs mountaineering classes at COCC

Outdoor classes offered by COCC

Retired banker introduces TraditionalMountaineering at COCC

Robert Speik's founding principles for a mountaineering club

![]()

Bob Speik founds an alpine mountaineering club

Glacier travel and crevasse rescue seminar training

Forest Service award goes to Robert Speik in 1996

Sierra Club Awards go to Robert Speik in 1985

YOUR ESSENTIAL SUMMIT PACK

What are the new Ten Essential Systems?

What does experience tell us about Light and Fast climbing?

What is the best traditional alpine mountaineering summit pack?

What is Light and Fast alpine climbing?

What do you carry in your day pack?

Photos?

![]()

What do you carry in your winter day pack?

Photos?

![]()

What should I know about "space blankets"?

Where can I get a personal and a group first aid kit?

Photos?

YOUR LITE AND FAST BACKPACK

Which light backpack do you use for winter and summer?

Analysis

pdf

![]()

What would you carry in your backpack to climb Shasta or Adams?

![]()

What is the best traditional alpine mountaineering summit pack?

Photos of lite gear packed for a multi day approach to spring and summer summits

Backpack lite gear list for spring and summer alpine mountaineering

4 pdf pages

ESSENTIAL PERSONAL GEAR

What clothing do you wear for Light and Fast winter mountaineering?

What do you carry in your winter day pack?

Photos?

![]()

Which digital camera do you use in the mountains?

What about Boots and Shoes?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() WARNING - *DISCLAIMER!*

WARNING - *DISCLAIMER!*

Mountain climbing has inherent dangers that can in part, be mitigated