™

™TRADITIONAL MOUNTAINEERING ™

™

™

FREE BASIC TO ADVANCED ALPINE MOUNTAIN CLIMBING INSTRUCTION

™

Home

| Information

| Photos

| Calendar

| News

| Seminars

| Experiences

| Questions

| Updates

| Books

| Conditions

| Links

| Search

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Congratulations Steve and Vince!

Congratulations Steve and Vince!

![]()

![]()

![]()

Nanga Parbat's infamous Rupal Face, a vertical 13,500' challenge of snow, rock and ice,

is widely considered the greatest alpine wall in the world!

Rupal Face of Nanga Parbat, widely considered the greatest alpine

wall in the world. House-Anderson Route, 2005

A NEW ROUTE ON THE RUPAL FACE CLIMBED IN ALPINE STYLE BY

VINCE ANDERSON AND STEVE HOUSE

Nanga Parbat, 8125m. The Central Pillar of the Rupal Face.

September 1-8, 2005. Anderson/House. (4,100m, M5/5.9, WI4)

This timeline of the Anderson/House climb was sent to the Patagonia home

office from Islamabad by Steve House on September 13th, 2005.

On 6 September, 2005, at 17:45 Vince Anderson and I stood on the windless

summit of Nanga Parbat after six days of climbing. We had climbed a new, direct

route on the Rupal Face. Famous for being one of the biggest, if not the

biggest, wall in the world and because it saw its first ascent in 1970 by

Reinhold and Gunther Messner.

Vince and I started at 4:00 a.m. on September 1 carrying 16kg of equipment each.

We had pared the equipment to the minimum we thought was necessary. We carried a

1kg tent and one synthetic sleeping bag that I sewed especially for this route.

We had the minimum of food and fuel. Our rack consisted of 3 cams, 10 nuts, 9

titanium pitons, 5 ice screws, and 10 runners. We climbed on a 8mm rope and

carried a 5mm static rope to use for the many rappels back down the face. Each

was cut to 50 meters long.

August 31

4 a.m. We left basecamp to start the route. The weather forecast is good for 7

days. At about 6:30 a.m. we arrived at the Bazhin glacier (the start of the

face). Numerous snow avalanches were releasing on the face after receiving sun

for the first time in many weeks. After watching for a bit, we decided to allow

the face to clean itself for a day. We returned to basecamp and the weather was

hot, dry, and clear all day.

September 1

4:00 a.m. We again left basecamp, this time for real. Around 6 a.m. we picked up

our gear we cached at the glacier and started up the lower slopes of the face.

It was much quieter now, it seemed that most of the snow avalanches had run the

previous day.

The warmth came on quickly as another hot and dry day was upon us. We worked

through some crevasses at the bottom of the face while trying to avoid exposure

from the large ice avalanched from the seracs above (the guillotine). After one

hour on the glacier we were on a prominent rocky rib that provides safety. We

followed the rib for several hundred meters before being forced out left and

back into a large couloir. Now avalanches were running frequently down the

couloir, but were restricted in their course by a deep channel in the snow. We

were able to stay to the side of the channel for a few hundred meters more, then

were forced to cross it between sloughs. It only took a few moments to cross,

but it proved to be exciting nonetheless as avalanches came rushing down the

flume with increasing frequency as the day progressed. Now we continued

cramponing up 40-degree snow for several hundred meters more until we had to

re-cross the channels (now there were two of them). We did so quickly, and again

were back on the rocky buttress. At the top of the buttress we were at about

5,100 meters and even with the bottom of the next rocky step, which is the crux

of the route. We traversed a snow slope to the base of the slope and found a

good bivy in the bergschrund there. This is the same bivy site Bruce and Steve

used in 2004. It was hot and there was plenty of melt- water running so we could

fill up without melting snow on the stove.

September 2

We left the bivy at 3:00 a.m. in the dark to avoid exposure to rockfall. There

was ice in the section immediately above the bergschrund that required us to

belay several hundred feet where Steve and Bruce had soloed in 2004. By the time

we arrived at the crux, it was in full sunlight and rocks were beginning to

fall. The pitch consisted of a snow-filled steep corner and the rock was covered

with a new glazing of ice. The ice was not thick enough, or solid enough, for

screws and often picks would shear through it. Snow covered the underlying rock

and made it difficult to dry-tool and find protection. Protection was very

inadequate on this pitch and the climbing was tedious. After spending much time

climbing and protecting it to half-height Vince needed a break and lowered off a

good piece to let Steve finish the pitch.

Steve opted to lead without a pack (and haul). This made things a bit easier for

him, but still the protection was scarce and the climbing serious. He dry-tooled

a section of loose and slopey rock (5.9). This pitch took us several hours to

complete and all the while volleys of stones and ice would periodically rain

down upon the belay. After the crux there were several more mostly easy pitches

to the top of the rock buttress. We simul-climbed much of this section. It was

now 1:00 p.m. and we had been out for 10 hours. We elected to bivy here, as it

was safe, despite having gained only 300 meters from the last bivy. This is also

the same place Steve and Bruce bivied in 2004 on their second night. Again we

reaped the benefit of the warm weather and filled our pot with melt-water.

September 3 - The eighteen-hour day

At 5 a.m. we left camp. We ascended a short snow ramp above camp and traversed

across an avalanche runnel that ran big several times during the previous night

due to serac-avalanches. From here we continued climbing 45-degree snow below

another rock buttress and traversed another avalanche runnel. At this point we

diverged from the 2004 route. We decided to do that because the 2004 route

seemed dangerous due to high snow levels in 2005 and direct pillar is a more

aesthetic and difficult line. The excitement of trying a new line that had some

serious question marks about it won out.

Several hundred more meters of steep snow brought us to the base of a rock

buttress and safety from avalanches. A few moderate mixed pitches got us onto

ice runnels above. We did many 150-meter simul-pitches just left of the ridge

crest and eventually the day ended. We continued climbing in to the night, now

pitch by pitch. We encountered one difficult mixed pitch of snow and steep loose

rock. Steve led this pitch and puked at the belay afterwards. From here we could

traverse right onto the hanging glacier that is one of the keys to this route.

We found a wild, but safe, bivy under a serac. It was 11:00 p.m. and we were

both very tired from the effort. We were at approximately 6,200 meters.

September 4 - Key Passage

After sleeping in, we left camp around 10:30 a.m. We ascended easy snow slopes

above the bivy that eventually yielded to 45-degree snow and ice. The rock

headwall above was steep and we needed to find an easy passage through it. A

little ways up, we found a nice WI 3 ramp leading through to the left. This was

a key section that looked possibly impassable from photos, so it was a relief to

find this section of water ice. As we climbed this, the day came to an end and

we began looking for a place to bivy. Steve led up snow and ice to the ridge on

our left in hopes of finding a good snow to make a tent platform. As he mounted

his steed, a large piece of it fell out beneath him. A single tool placement in

snow saved him from a huge whipper and large chunks of snow hammered Vince. A

bit further on, we found a spot on the ridge that could be leveled to the width

of the tent, barely. The ledge was tiny and precarious, so we stayed tied in for

the night should the snow underneath cut loose. We were at approximately 7,000

meters.

September 5

Again a 10:30 a.m. start due to the length of the previous days effort. We

rapped from our perch back to the snow slopes below. From here, we began heading

up easy ice to the upper snow slopes of the ramp system we were on. The altitude

effect was obvious here and we were moving slow. We plodded away up these slopes

and gained the crest of the ridge just below a short mixed passage leading to

the upper snow slopes very near to where Steve and Bruce had turned back the

previous year. We were also right above the Merkl Icefield. We made our high

camp here at 7,400 meters.

September 6 - Summit Day

At 3:30 a.m. we set off for our summit attempt with one light pack between the

two of us with 3 liters of water, 2 liters of Spiz (energy mix), several packs

of GU each and 50 meters of 5mm cord.

After two pitches of mixed climbing, we began plodding up deep, steep,

unconsolidated, faceted snow. This process was extremely slow, difficult, and

discouraging. After 100 meters of this, the snow surface had strengthened enough

to allow us to travel on top.

We continued up moderately steep snow and ice until we were able to gain a rocky

ridge crest to our left. It was slow moving up the easy mixed terrain on the

ridge. The weather was superb, it was even slightly hot.

By mid-day, we joined the upper Messner route at around 7,900 meters. We could

see faint hints of the Korean climbers' tracks from July. This eventually

brought us to easy snow and by 4:00 p.m. we arrived at the false summit. There,

at 8,000 meters, Steve took off his boots to dry off his socks in the sun and

Vince took a 5-minute nap.

At 5:45 p.m. we arrived at the summit. We savored a few minutes together, took

in the marvelous views in all directions, shot some photographs and at 6:00 p.m.

descended from the summit. We made it down the easy summit snowfields before

darkness caught us. We continued descending our route of ascent, rappelling many

sections with our 50 meters of rope until we reached the top of the two mixed

pitches above camp where we had another rope. Two rappels from here and a short

walk had us both back to camp at 3:00 a.m., 24 hours after starting. We made

some water and promptly went to sleep.

September 7

After a light night's sleep we left camp around 8:00 a.m. We began by doing 6

steep rappels down to the Merkl Icefield to join the 1970 Messner route. Upon

reaching the Merkl, we found a tent abandoned by the Koreans.

We continued down-climbing the Merkl Icefield and eventually began rappelling.

We reached the approximate height of camp 2 (ca. 6,000 m.) by nightfall and

continued descending. By 11:00 p.m. we reached what we thought to be the site of

camp 1 (ca. 5,500 m.) and bivied under a serac. Steve's headlamp batteries were

failing and Vince inadvertently dropped his lamp forcing us to sleep here.

We could see many large bonfires awaiting us below and hear the local villagers

drumming in celebration.

September 8

After a coughing-fit filled night, we woke around 7:00 a.m. and continued our

slow descent to base camp. Exhausted from 8 days on the go and precious little

sleep, we arrived in camp around 2:00 in the afternoon to the great excitement

of our Liaison Officer and other locals.

Afterwards:

We have been overwhelmed by the local response to our ascent. All the way out to

the road head locals stopped us and congratulated us. In Tarshing (the road

head), about 200 schoolchildren turned out to greet us with bouquets of flowers,

posters commemorating our climb, and flower leis. The town had a ceremony and

the mayor and school headmasters all made speeches. Wild! It turns out the whole

valley was watching our progress by seeing our headlamps each night. And the

summit day was so clear, many people watched us summit through binoculars.

Summary:

Nanga Parbat. The Central Pillar of the Rupal Face. Sept 1-8, 2005.

Anderson/House. (4,100m, M5/5.9, WI4)

A note from Steve and Vince: Note that if you measure the face from the

Bazhin Glacier right where the face starts, it is 4,125 meters. Some people

measure the face as 5,000 meters, but to get 5,000 meters you have to measure

from the village of Tarshing where you start the trek to basecamp. 4,100 meters

seems to us like an honest measurement of the amount of climbing on the face.

http://www.patagonia.com/culture/fieldreports/2005/steve_house.shtml

RUPAL FACE II: A NEW ROUTE ON THE RUPAL FACE CLIMBED IN ALPINE STYLE

FOR GRIVEL, BY STEVE HOUSE

On 6 September, at 17:45 Vince Anderson and I stood on the windless summit of

Nanga Parbat after six days of climbing. We had climbed a new, direct route on

the Rupal Face. Famous for being one of the biggest, if not the biggest, wall in

the world and because it saw its first ascent in 1970 by Reinhold and Gunther

Messner.

The Rupal Face of Nanga Parbat with the Anderson-House line of September 2005

shown

Vince and I started at 4:00 on 1 September carrying 16kg of equipment each. We

had pared the equipment to the minimum we thought was necessary. We carried a

1kg tent and one synthetic sleeping bag that I sewed especially for this route.

We had the minimum of food and fuel. Our rack consisted of 3 cams, 10 nuts, 9

titanium pitons, 5 ice screws, and 10 runners. We climbed on a 8mm rope and

carried a 5mm static rope to use for the many rappels back down the face. Each

was cut to 50 meters long.

The first two nights we followed the route climbed by myself and Bruce Miller in

2004. (to 7,500m, no summit). On the third day, searching for more of an

adventure than merely completing the 2004 line and dealing with more snow on the

wall that we found in 2004, Vince and I headed straight up the prominent pillar

in the center of the face.

That day we climbed many pitches. (We lost count around 15, and if you counted

the simu-climbing it was probably more than 30) After 18 hours of climbing we

finally reached a place where we could bivouac.

I was most nervous about the next day. So far we had climbed a mostly-safe,

beautiful direct line. But the photos I had and the reconnaissance I had done

had revealed no easy way through the rock barrier above us. After several hours

of mostly moderate ice climbing which we soloed, we took a break just below the

key section. I was hoping for an ice line that we could climb quickly. And after

a deep breath, I set off to the right, and was rewarded by the site of a grade 3

or 4 icefall above us. I was so happy, and so keen to make this section go as

quickly as possible, I soloed the 50 meters of steep ice with my pack while

Vince waited below. At that moment I felt like I was flying above the mountains,

I was so happy to find this key passage. After climbing the pitch I lowered the

rope to Vince and belayed him up to me.

I stayed in lead for the rest of the afternoon and the coming night. As quickly

as possible we climbed up through several more steep (but not as serious) steps

of ice. Conditions were excellent, but we needed to find a bivouac soon.

This is when we had our closest brush with disaster. We were simu-climbing with

me in the lead and I was trying to get on top of a narrow ridge in hopes of

discovering some place to set the tent. While mounting the cornice, it broke out

from underneath me. Me feet swung free and one of my ice axes pulled out. By

luck my other ice tool stayed put and I got my feet back in and quickly swung

over onto the other side of the very narrow ridge, which unfortunately was just

as steep on the other side. The big pieces of hard snow hit Vince and

fortunately he did not get pulled off. If he had I am sure my one tool would not

have held both of us and my last ice screw was more that 20 meters below me. It

was a very dangerous moment.

In the end we were able to cut off the top of the ridge just 20 meters higher

and pitch the tent in a very small and exposed (but flat) place.

In the morning we rappelled back to the main ice gully and continued to our high

bivouac at approximately 7,400 meters. This day was tiring only because of the

altitude as the technical difficulties eased the higher we climbed.

Summit day was physically one of the hardest days I have ever had in the

mountains. We had climbed for five days with very limited chance for recovery.

Fortunately the weather was perfect. But I was not sure that we would succeed

until we arrived just below the south summit at over 8,000 meters and could see

the last easy meters to the top.

The descent ran late into the night. We made mistakes and climbed slowly. Nearly

losing our 5mm rope at one point and having difficulty with the rappels which

seemed to be always getting tangled and stuck.

In the morning we packed as soon as we could and organized for the descent. Our

plan was to rappel the steep wall below us to the Merkyl Icefield where we would

join the 1970-Messner route and follow that route to the base of the wall. The

weather was still good, but during the afternoons the clouds showed some sign

that would end soon.

We made many rappels that day and down climbed as much as possible. We continued

late into the night. Finally halting about 2,000 meters lower than we started

(approx 5,500m) when Vince dropped his headlamp and my batteries began to fail.

The next day we sluggishly made our way down to the valley, meeting our Liaison

Officer and several excited locals near the 1970 basecamp in the early

afternoon. After one full day of rest we had to pack up and trek out in order

for Vince to make his flight on the 14th which would allow him to get to work as

a guide examiner on 16 September.

Summary:

Nanga Parbat, 8125m. The Central Pillar of the Rupal Face. 1-8 September, 2005.

Anderson/House. (4,100m, M5 X, 5.9, WI4).

Note that if you measure the face from the Bazhin Glacier right where the

face starts, it is 4,125 meters. Some people measure the face as 5,000 meters,

but to get 5,000 meters you have to measure from the village of Tarshing where

you start the trek to basecamp. 4,100 meters seems to us like an honest

measurement of the amount of climbing on the face.

http://www.grivelnorthamerica.com/headlines.php?id=34

A dream climb

It took a Bend mountaineer 15 years, but he's finally helped blaze a

new path up one of the world's tallest mountain faces

The Bulletin

By Abbie Bean

November 22, 2005

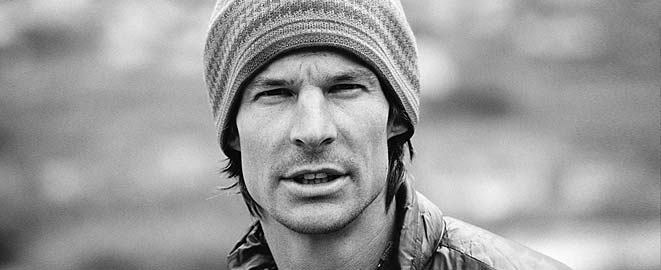

Exactly 15 years ago, climber Steve House got his first, live look at the

tallest mountain face on the planet: the 13,500 foot Rupal face on Pakistan's

Nanga Parbat.

Exactly 15 years ago, a dream was born.

Exactly 15 years later, House opened a new route on the Rupal face, billed the

Central Pillar route, and became part of one of the first teams to ascend the

face in alpine style.

At the time House first set his sights on 26,660-foot Nanga Parbat, the ninth

tallest mountain in the world, he was a 20-year old college student on a

Slovenian expedition, and still a relative novice as a climber and mountaineer.

After starting to climb with his father, House gained experience between high

school in his hometown of La Grande and college at Evergreen State in Olympia,

Wash., while living in the former Yugoslavia, where he was studying as an

exchange student: As House tells it, climbing was big in Yugoslavia, which

inspired him to join his first climbing club abroad.

Today, House, 35, a Bend resident and contract employee for outdoor retail

company Patagonia, can now say not only he has fulfilled his dream of climbing

the Rupal face, but that he has made climbing history as well - by tackling the

face in alpine style.

Between September and September 8, 2005, House and his climbing partner, Vince Anderson of

Ridgway, Colorado., successfully pioneered a new route on the Rupal face, carrying

all their supplies to make the ascent of the route in one push.

They used no pre-established camps and no pre-established ropes to guide

climbers between camps. There was no returning to a lower camp to replenish

supplies before continuing upward. House and Anderson simply set up camp

wherever they were when they decided the day was done.

Just last year, House attempted the route in alpine style with fellow climber

Bruce Miller of Boulder, Colo., but they had to descend when House fell ill.

House says that he is an "alpine-style hardliner" for two reasons: "First, I

think it's environmentally important," says House, who has also climbed in the

Cascades" and the Canadian Rockies and has been on 27 climbing expeditions in

Alaska. "I just think it's wrong to leave a lot of .garbage on the mountains -

ropes, tents and ' oxygen bottles. Also, we already know we can climb any route

with enough technology. So what's the point? That's not interesting. Uncertainty

is the most important aspect (of climbing)."

House said he believes that climbing the highest mountains in the world is not

necessarily synonymous with accomplishing the world's greatest mountaineering

feats. He explains that what is important to him is the creative process used

when mountaineering, ascending routes that are more technically challenging, and

experiencing the beauty of the mountains.

"To observers and historians, this is my most important climb," says House

nonchalantly. "But for me personally, it was no better than some climbs I did

last year, except that everything went right."

After laying the philosophical groundwork for the story of his latest

expedition, House begins to flesh out the tale with details of his assault on

the Rupal face:

There were four men at base camp: House and Anderson, who would be climbing one

route up the Rupal face, and two other men attempting a different route up the

face.

House said a minimum of four climbers were needed at base camp to make the trip

financially, feasible. It 'was $4,500 for House and Anderson to obtain their

permit to climb the Rupal face, and they needed an additional $9,800 to finance

the rest of the trip.

House said Anderson and he began their ascent in September, when weather

conditions were likely to be most favorable in Pakistan. Throughout the climb,

the weather was perfect.

According to House, the duo carried nothing unnecessary in their packs, one of

which weighed 10 pounds and the other 25 pounds. House would take the lighter

pack occasionally, leading the climb and negotiating its technical challenges.

Then Anderson would' carry the lighter pack and take his turn turn at leading.

In addition to the packs, the climbers were strapped with everything from ice

axes to climbing ropes.

House describes the ascent as extremely draining, and he reports losing 15

pounds over the course of the eight day climb. During the day, House and

Anderson ate energy foods, bars and gels, and nightly meals consisted' of a cup

of soup and dried mashed potatoes with olive oil.

"Alpine style is pure," says House. "It takes more commitment."

By September 6, the climbers' commitment had paid off. They reached the summit of

the Rupal face at 5:45 p.m., in just six days.

"It was one of the most memorable moments of the trip," recalls House. I had my

eye on the route for a long time. I'd arranged my entire life around

this goal. I did anywhere from 26 to 28 hours of training on a hard week. I had

to finance the trip. I had to take time off from work."

Just six weeks after the final day of the Rupal face descent, House is lounging

on the couch in. his girlfriend Jeanne's home off Newport Avenue, recovering

from a long day of climbing at Smith Rock State Park. The next day he plans to

go elk hunting -a childhood hobby-with his uncle and nephew.

"It's just in my. heart to do it," he says of his dedication to climbing. "I

love climbing, (setting up the gear), achieving goals or not achieving them. The

more you put into climbing, the more it gives back to you, I think."

Soon, House will resume work for Patagonia, where he has been involved in

product development and grass-roots marketing. He also continues to teach

climbing clinics and present climbing slide shows at Patagonia-sponsored

festivals.

"This has been my favorite job so far," says House, who has also worked as a

mountain guide in Washington, and as an avalanche forecaster for the, Cascades.

In addition, House hopes to continue to complete two major expeditions per year.

But for now he can rest knowing he has accomplished one of his greatest goals,

even though he feels the truest rewards of mountaineering are not found in the

afterglow.

"The most rewarding part is the experience itself " House said. ,"I am happy I

did it, but there: is also a bit of an empty feeling now. I am feeling a little lost."

Note: Nanga Parbat's infamous Rupal Face , a vertical 13,500 foot challenge of snow, rock and ice is widely considered the greatest alpine wall in the world. This very big climb has been (so far) reported briefly in Issue 244, December 2005, Climbing Magazine. The pure success of House and Anderson is contrasted in the media with the failed climb of of the celebrated Slovenian climber Tomaz Humar who was rescued from the Rupal Face by a high altitude French helicopter with huge media coverage in August 2005, about a month before Steve and Vince walked back to camp. (National Geographic Adventure Magazine covers the now controversial Tomaz Humar rescue in its December 2005 issue.) --Webmeister Speik

HOUSE-BACKES-TWIGHT ON CZD

Steve House, Scott Backes and Mark Twight climbed the Czech Direct on Denali

N13 Czech Direct Alaskan Grade 6+

Adarn, Krizo and Korl 1984.

This is objectively safer but technically

harder than the other South Face routes, with sustained difficulties, 60-100°

ice and 5.6 rock and poor bivouac sites on the first 1500m (5000ft). About 12-21

days.

June 24-26 Steve House, Scott Backes and Mark Twight climbed the Czech Direct on

Denali. The first ascent, in 1986, required 11 days and approximately 1000'

of fixed rope. Kevin Mahoney and partner (Ben Gilmore) made the second ascent

over 8 days in May, 2000. The Backes/ House/ Twight team climbed it in 60 hours

non-stop. They carried no bivouac gear apart from a 2lb Down or Polarguard

jacket each. The trio brought two stoves in order to melt enough snow to stay

hydrated. Starting with just 22oz of fuel for each, these ran out of gas at hour

48. A total of 55lbs was split between two packs, (18lbs were water), leaving

the leader pack-free to move fast.

The Czech Direct is 9000' high. But only 5500' present any climbing difficulty:

ice climbing up to WI6 and rock to UIAA V+ (USA 5.9). The team belayed 31 (60m)

pitches, simul-climbed some terrain and soloed the rest including the first

1000' where the Czechs belayed 9 pitches. After crossing the bergschrund at 06h

Backes, House and Twight passed the Czech's second bivouac site at 08h. They

found many good quality pitches. Twight exclaims, "It was fantastic climbing and

there was a lot of it. The Czech topo showed 24 pitches of UIAA III (USA 5.4) or

harder. Ice conditions were such that we never holstered our tools - but we did

have to file them twice during the

climb."

Twenty-four hours into it, almost 4000' up the route the trio passed the point

of no return. The Czechs had climbed 43 pitches to reach the same spot. Twight

said, "we didn't have enough gear to retreat, the terrain would have swallowed

us. That we had to go up was liberating and terrifying, both".

The concurrent arrival of poor visibility, the 34th hour's low blood sugar and

the proximity of a serac known as "Big Bertha" caused a route-finding error at

around 15,900'. "We behaved like beginners, trying different ways through the

last rock-band," says Twight. "We didn't want to be anywhere near the serac so

we trended west. Finally, we sat down to brew and think objectively. The route

was actually obvious - further east, right next to Big Bertha. It was safer than

it sounds."

But the team was hammered, "I caught House snoring at one belay" Twight recalls.

"It's the beautiful thing about climbing as a team of three: one leads, one

belays and the other passes out in his harness."

Difficulties ended at 16,800'. The original Czech line remains independent,

following easy snow slopes cris-crossed by crevasses to the summit. Instead,

Backes, House and Twight simul-climbed to 17,400' where they joined the Cassin

Ridge at 14h and unroped. Sixty hours after crossing the bergschrund they

traversed onto "Pig Hill" just beneath Kahiltna Horn, 200' below the summit.

Twight admits, "it's the first time I regret missing a summit. Our effort

deserved a better finish but we were fairly wasted by that point." Despite this

the team made it down the West Buttress to the National Park Service camp at

14,000' in 2hrs 20min. "We slept and ate for 24 hours there before recovering

our skis from a cache at 11,000' and sliding back to the airstrip at 7200'.

Backes summed the climb up by saying, "The CZD is certainly one of the best

mixed climbs in the world. It's crazy that it went unrepeated for 14 years."

House stated simply, "It was my first world-class route," as if the other routes

he's done in Alaska, the Yukon and Canadian Rockies are anything less.

Twight concludes, "psychologically it was quite intense. Steve had climbed

continuously for 36 hours on King Peak. Scott and I had gone 41 hours without

sleep on Mount Hunter in 1994. 60 hours of non-stop climbing was a huge step for

all of us. Sleep deprivation, combined with the constant demand for a high level

of awareness transported

us to an unfamiliar place. The cramps were fierce and the aural hallucinations

memorable. Ultimately, I think, beyond a certain point, exhaustion has its way

with a climber; we dropped some gear - a cam, a screw, and an ice tool - and got

lost. Everyone's mental ability to lead more than two pitches in a row was

compromised by hour 40. On the other hand, if someone could go lighter than us

they could climb it faster."

http://www.risk.ru/eng/mount/reports/czech/

![]()

Read more . . .

Steve House

Beth Rodden and Tommy Caldwell

Dan Osman

Conrad Messner

Tomaz Humar

About Alpine Mountaineering:

The Sport of Alpine Mountaineering

Climbing Together

Following the Leader

The Mountaineers' Rope

Basic Responsibilities

![]() Cuatro Responsabiliades Basicas de Quienes Salen al Campo

Cuatro Responsabiliades Basicas de Quienes Salen al Campo

The Ten Essentials

![]() Los Diez Sistemas Esenciales

Los Diez Sistemas Esenciales

TECHNICAL MOUNTAINEERING

What is the best traditional alpine mountaineering summit pack?

What is the best belay | rappel | autoblock device for traditional alpine mountaineering?

What gear do you normally rack on your traditional alpine mountaineering harness?

Photos?

![]()

What is the best traditional alpine mountaineering seat harness?

Photos?

Can I use a Sharpie Pen for Marking the Middle of the Climbing Rope?

What are the highest peaks in Oregon?

Alphabetically?

CARBORATION AND HYDRATION

Is running the Western States 100 part of "traditional mountaineering"?

What's wrong with GORP?

Answers to the quiz!

Why do I need to count carbohydrate calories?

What should I know about having a big freeze-dried dinner?

What about carbo-ration and fluid replacement during traditional alpine climbing?

4 pages in pdf

![]()

What should I eat before a day of alpine climbing?

ALPINE CLIMBING ON SNOW AND ICE

Winter mountaineering hazards - streams and lakes

Is long distance backpacking part of "traditional mountaineering"?

How long is the traditional alpine mountaineering ice axe?

What about climbing Mt. Hood?

What is a good personal description of the south side route on Mount Hood?

What should I know about travel over hard snow and ice?

How can I learn to self belay and ice axe arrest?

6 pdf pages

![]()

What should I know about snow caves?

What should I know about climbing Aconcagua?

AVALANCHE AVOIDANCE

Young Bend man dies in back county avalanche

What is an avalanche cord?

Avalanche training courses - understanding avalanche risk

How is avalanche risk described and rated by the professionals?

pdf table

How can I avoid dying in an avalanche?

Known avalanche slopes near Bend, OR?

What is a PLB?

Can I avoid avalanche risk with good gear and seminars?

pdf file

SNOWSHOES AND CRAMPONS

Why do you like GAB crampons for traditional mountaineering?

What should I know about the new snowshoe trails

What are technical snowshoes?

Which crampons are the best?

What about Boots and Shoes?

![]()

YOUR ESSENTIAL SUMMIT PACK

What are the new Ten Essential Systems?

What does experience tell us about Light and Fast climbing?

What is the best traditional alpine mountaineering summit pack?

What is Light and Fast alpine climbing?

What do you carry in your day pack?

Photos?

![]()

What do you carry in your winter day pack?

Photos?

![]()

What should I know about "space blankets"?

Where can I get a personal and a group first aid kit?

Photos?

YOUR LITE AND FAST BACKPACK

Which light backpack do you use for winter and summer?

Analysis

pdf

![]()

What would you carry in your backpack to climb Shasta or Adams?

![]()

What is the best traditional alpine mountaineering summit pack?

Photos of lite gear packed for a multi day approach to spring and summer summits

Backpack lite gear list for spring and summer alpine mountaineering

4 pdf pages

ESSENTIAL PERSONAL GEAR

What clothing do you wear for Light and Fast winter mountaineering?

What do you carry in your winter day pack?

Photos?

![]()

Which digital camera do you use in the mountains?

What about Boots and Shoes?

![]()

TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE

How did you become interested in traditional mountaineering techniques?

Who is Conrad Messner?

What is traditional slacklining or highlining?

What are some of the comments you have received?

Who was Peter Starr?

Who are the Mazamas?

What is an avalanche cord?

Who were the notorious Vulgarians?

How was top rope climbing practiced in the 1970s?

What is a Whillans sit harness?

What is a dulfersitz rappel?

How do I self-belay a rappel?

BACKCOUNTRY NAVIGATION

How accurate is the inexpensive hand-held GPS today?

What are some good Central Oregon Geocaches?

What is the Public Land Survey Grid?

pdf

What is the UTM Grid?

six pdf pages

Which GPS do you like?

![]()

Which Compass do you like?

![]()

How do you use your map, compass and GPS together, in a nut shell?

How can I learn to use my map, compass and GPS?

Do you have map, compass and GPS seminar notes?

six pdf pages