™

™TRADITIONAL MOUNTAINEERING

™

www.TraditionalMountaineering.org

™ and also

www.AlpineMountaineering.org

™

™

™

FREE BASIC TO ADVANCED

ALPINE MOUNTAIN CLIMBING INSTRUCTION™

Home

| Information

| Photos

| Calendar

| News

| Seminars

| Experiences

| Questions

| Updates

| Books

| Conditions

| Links

| Search

![]()

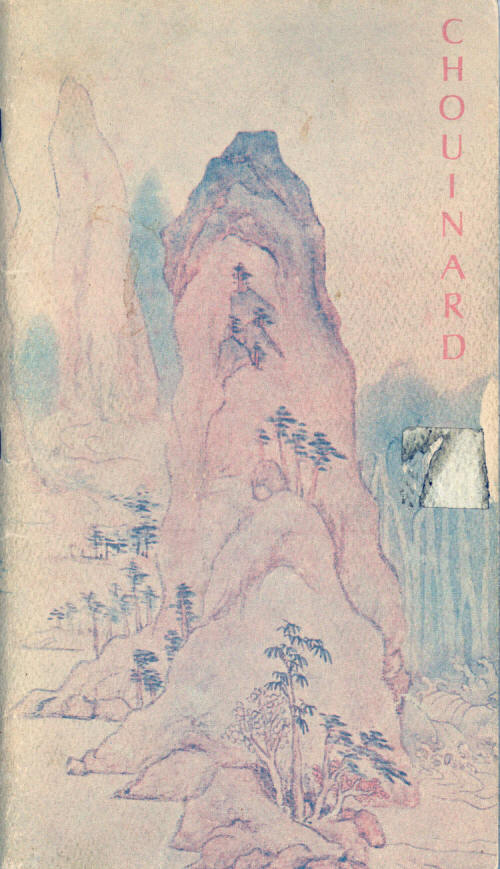

The 1972 Chouinard Catalog introducing hexentrics, stoppers, the "sit harness" and more

Image Copyright© 2005-2012 by Robert Speik. All Rights Reserved.

This is the actual size of the catalog!

This copy of the 1972 Chouinard catalog was mailed to me at my home. My name and address

are on the label still attached to the back cover.

-Robert Speik

Check out the complete Chouinard 1972 Catalog reproduced on RAHutchins web

site:

www.ClimbAZ.com

Bob Hutchins writes:

David Brashears, the legendary climber/mountaineer and IMAX photographer, writes

about the influence of the 1972 Chouinard catalog in his 1999 autobiography,

"High Exposure":

"Another serious influence on my developing style came via the Chouinard

climbing equipment catalogue of 1972, a slender publication with a Chinese

landscape painting on the cover. Its author, the revered rock and ice climber

Yvon Chouinard, called for "clean" climbing, proposing that climbers disavow

pitons and bolts that scarred or otherwise altered rock. Instead, he advocated

the use of metal nuts of various shapes and sizes which slotted into cracks

without damage to the rock and could be recovered by the second climber on a

rope. He reminded readers of the edict of John Muir, the late-nineteenth-century

poet-environmentalist: "Leave no mark except your shadow."

This ethic of purism and self-control made a profound impact on the climbing

community - and on me as well."

--David Brashears

Yvon Chouinard

Beginnings and Blacksmithery

Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia's founder, got his start as a climber in 1953 as a

14-year-old member of the Southern California Falconry Club, which trained hawks

and falcons for hunting. After one of the adult leaders, Don Prentice, taught

the boys how to rappel down the cliffs to the falcon aeries, Yvon and his

friends became so fond of the sport they started hopping freight trains to the

west end of the San Fernando Valley, to the sandstone cliffs of Stony Point.

There, eventually, they learned to climb up as well as rappel down the rock.

Chouinard started hanging out at Stony Point on every weekend in the winter, and

at Tahquitz Rock above Palm Springs in the fall and spring. There he met some

other young climbers who belonged to the Sierra Club, including TM Herbert,

Royal Robbins, and Tom Frost. Eventually, the friends moved on from Tahquitz to

Yosemite, to teach themselves to climb its big walls.

The only pitons available at that time were made of soft iron, placed once, then

left in the rock. But in Yosemite, multi-day ascents required hundreds of

placements. Chouinard, after meeting John Salathé, a Swiss climber and

Swedenborgian mystic who had once made hard-iron pitons out of Model A axles,

decided to make his own reusable hardware. In 1957, he went to a junkyard and

bought a used coal-fired forge, a 138-pound anvil, some tongs and hammers, and

started teaching himself how to blacksmith.

Chouinard made his first pitons from an old harvester blade and tried them out

with T.M. Herbert on early ascents of the Lost Arrow Chimney and the North Face

of Sentinel Rock in Yosemite. The word spread and soon friends had to have

Chouinard's chrome-molybdenum steel pitons. Before he knew it he was in

business. He could forge two of his in an hour, and sold them for $1.50 each.

Chouinard built a small shop in his parents' backyard in Burbank. Most of his

tools were portable, so he could load up his car and travel the California coast

from Big Sur to San Diego, surfing. After a session, he would haul his anvil

down to the beach and cut out angle pitons with a cold chisel and hammer before

moving on.

For the next few years, Chouinard forged pitons during the winter months, spent

April to July on the walls of Yosemite, then headed out of the heat of summer

for the high mountains of Wyoming, Canada, or the Alps, and then back to

Yosemite in the fall until the snow fell in November. He supported himself

selling gear from the back of his car. The profits were slim, though. For weeks

at a time, he'd live on fifty cents to a dollar a day. Before leaving for the

Rockies one summer he bought two of cases of dented, canned cat tuna from a

damaged-can outlet in San Francisco. This food supply was supplemented by

oatmeal, potatoes, and poached ground squirrel and porcupines.

In Yosemite, Chouinard and his friends were called the Valley Cong. They had to

hide out from the rangers in the boulders above Camp 4 after they overstayed the

2-week camping limit. They took pride in the fact that climbing rocks and

icefalls had no economic value, that they were rebels. Their heroes were Muir,

Thoreau, Emerson, Gaston Rebuffat, Ricardo Cassin, and Herman Buhl.

Chouinard Equipment

There was soon enough demand for Chouinard's gear that he couldn't keep making

it by hand; he had to start using tools and dies and machinery. So in 1965, he

went into partnership with Tom Frost, who was an aeronautical engineer as well

as a climber, and had a keen sense of design and esthetics. During the nine

years that Frost and Chouinard were partners, they redesigned and improved

almost every climbing tool, to make them stronger, lighter, simpler, and more

functional. They would return from every trip to the mountains with new ideas

for improving existing tools.

Their guiding design principle came from Antoine de Sainte Exupéry, the French

aviator:

Have you ever thought, not only about the airplane but whatever man builds, that

all of man's industrial efforts, all his computations and calculations, all the

nights spent working over draughts and blueprints, invariably culminate in the

production of a thing whose sole and guiding principle is the ultimate principle

of simplicity?

It is as if there were a natural law which ordained that to achieve this end, to

refine the curve of a piece of furniture, or a ship's keel, or the fuselage of

an airplane, until gradually it partakes of the elementary purity of the curve

of the human breast or shoulder, there must be experimentation of several

generations of craftsmen. In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not

when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to

take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.*

By 1970, Chouinard Equipment had become the largest supplier of climbing

hardware in the U.S. It had also become an environmental villain because its

gear was damaging the rock. Climbing had become more popular, but remained

concentrated on the same well-tried routes in areas like El Dorado Canyon, the

Shawangunks, and Yosemite Valley. The same fragile cracks had to endure repeated

hammering of pitons, during both placement and removal and the disfiguring was

severe. After an ascent of the degraded Nose route on El Capitan, which had been

pristine a few summers earlier, Chouinard and Frost decided to phase out of the

piton business. This was to be the first big environmental step we would take

over the years. It was a huge business risk – pitons were then still the

mainstay of the business – but it had to be done.

Fortunately, there was an alternative: aluminum chocks that could be wedged by

hand rather than hammered in and out of cracks. We introduced them in the first

Chouinard Equipment catalog in 1972.

The catalog opened with an editorial from the owners on the environmental

hazards of pitons. A 14-page essay by Sierra climber Doug Robinson on how to use

chocks began with a powerful paragraph:

There is a word for it, and the word is clean. Climbing with only nuts and runners for protection is clean climbing. Clean because the rock is left unaltered by the passing climber. Clean because nothing is hammered into the rock and then hammered back out, leaving the rock scarred and the next climber's experience less natural. Clean because the climber's protection leaves little trace of his ascension. Clean is climbing the rock without changing it; a step closer to organic climbing for the natural man.

Within a few months of the catalog's mailing, the piton business had atrophied; chocks sold faster than they could be made. In the tin buildings of Chouinard Equipment, the steady pounding rhythm of the drop hammer gave way to the high-pitched, searing whine of the multiple-drill jig.

http://www.patagonia.com/culture/patagonia_history.shtml

Item #: OP405

CHOUINARD EQUIPMENT CATALOG 1972

By Chouinard, Yvon. Tom Frost, Doug Robinson

Price: $500.00

Detailed Product Description

The 1972 Chouinard Equipment Catalog marked a watershed in climbing

culture/technology by establishing a standard for clean climbing ethics in the

United States. In addition to lots of nice photos of gear, features in the

catalog include:

“A Word..” an essay on clean climbing by Yvon Chouinard and Tom Frost

A History of Chouinard Firsts with a photo of Yvon Chouinard and John Salathe in

1964

The essay, “The Whole Natural Art of Protection,” by Doug Robinson

Short pieces on “the Yosemite Method,” “A simple rappelling system and the

Yosemite Hammer,” Nailing Flexible Flakes,” “Method of Removing,” and “Safety

Considerations.”

There are a number of ads for Chouinard equipment. The front cover is a

reproduction of a sixteenth century Chinese painting. This 96-page Catalog

contains a number of lovely black and white photos of mountain scenes and

climbers. The dimensions are approx 6 3/8 x 11 in. Near Fine condition, except

that there is some superficial soiling to the front and rear covers and page

edges. No internal or external writing, no mailing label, no rips, no flaws.

www.chesslerbooks.com

Check out

http://climbaz.com/chouinard72/chouinard.html - every page of the catalog is

scanned in and discussed.

On the site is an interview with Steve Grossman

'Another thing that really affected me ethically early on was the 1972 Chouinard

climbing catalog. It made a strong push for clean climbing in terms of free

protection and people relying less on hammered protection. It had a lot of

affect on everybody pretty much in climbing at the time in a way that’s really

unparalleled. It laid out the ethics of British rock climbing. You have a small

island with a fairly finite amount of rock and a lot of heavy use. They really,

in contrast to what was happening in the rest of Europe, developed a low impact

ethic. It allowed their routes to see heavy traffic and minimal damage. The big

push was toward that same kind of ethic.

Fortunately, at the same time, Chouinard equipment came out with hexes and

stoppers, equipment that made all that kind of low impact climbing possible.

Prior to those innovations, the kind of nuts that were available out there were

just not really all that effective. The synergy of that catalog pushing that

ethic and equipment that was being produced revolutionized climbing as we know

it. Thinking about it now, had that not happened, and had people continued to

pound pins and bust flakes off and scar and damage rock, things would be much

uglier out there. It’s really pretty horrifying what would have gone on if that

revolution hadn’t happened.'

http://www.chesslerbooks.com/eCart/viewItem.asp?idProduct=3757

![]()

![]()

![]() WARNING - *DISCLAIMER!*

WARNING - *DISCLAIMER!*

Mountain climbing has inherent dangers that can in part, be mitigated

Read more . . .

What is the Willans sit harness?

Which harness is best for traditional

mountaineering and beak bagging?

Notable mountain climbing accidents revisited

![]()

The Sport of Alpine Mountaineering

Climbing Together

Following the Leader

The Mountaineer's Rope

![]()

Basic Responsibilities

The Ten Essentials

Our Mission

South, Middle, and the sinister North Sister and Broken Top, about 25 miles west of Bend, Oregon

Copyright© 2005-2012 by Robert Speik. All Rights Reserved.